During my Master of Teaching degree at the University of Melbourne, my table group had a running joke before class presentations: “scaffolding the proverbial.” A quick double karate-board chop sealed the moment—silly, yes, but motivating.

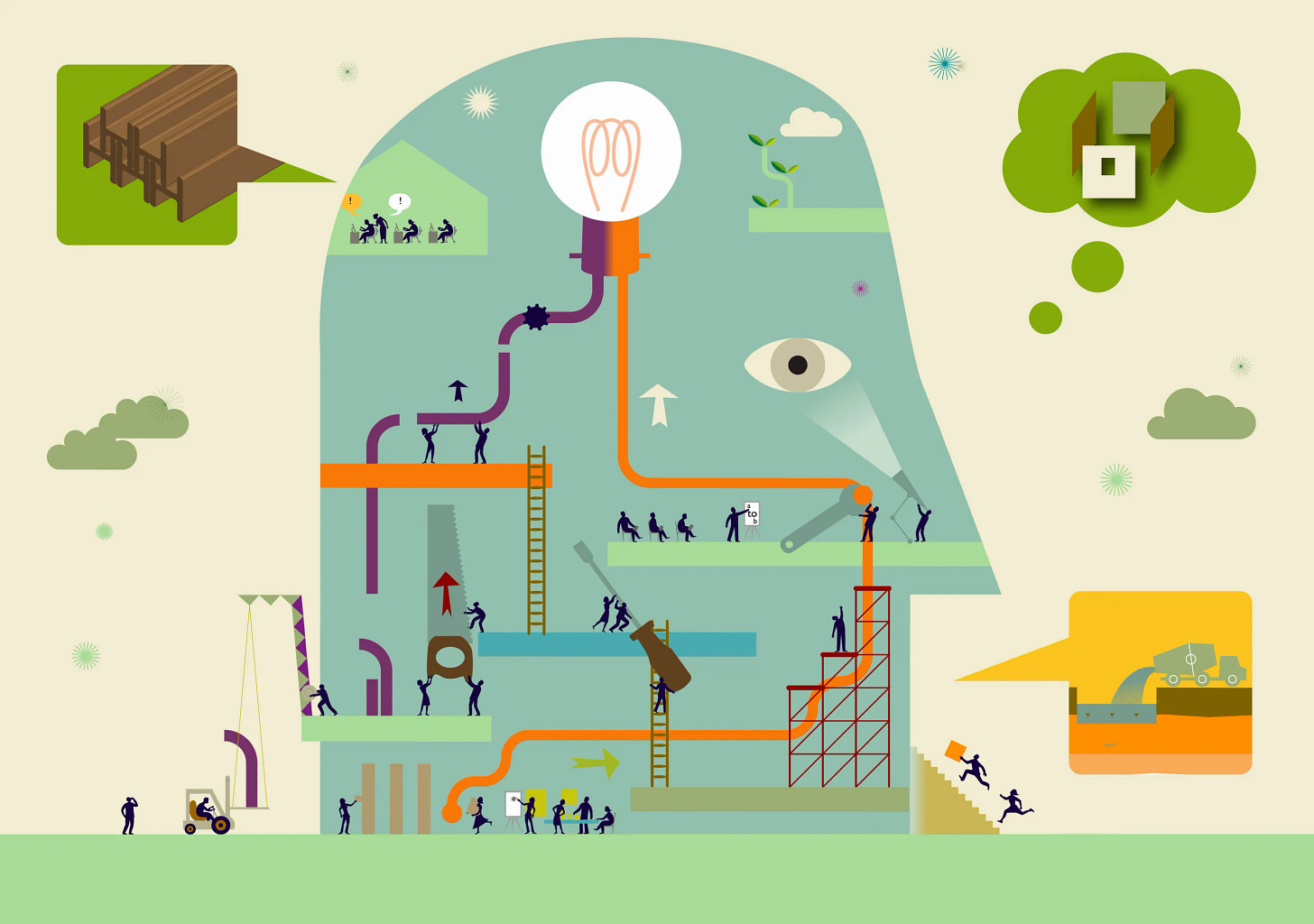

Scaffolding is classic teacher jargon, but at its core, it’s about building confident, capable, and resourceful learners. It can take many forms: structured lessons, direct instruction, questioning, or worked examples—all designed to gradually release responsibility to the learner.

This week, I’ve been revisiting a key text in this space—Better Learning Through Structured Teaching by Douglas Fisher and Nancy Frey—to ensure that my approach is on point.

Roadmap for This Post

Douglas Fisher and Nancy Frey’s “Gradual Release” instructional model

Sentence scaffolding for dysgraphia and mainstream education with “Ticking Mind” resources

Navigating Dysgraphia Club Updates

Better Learning Through Structure

Douglas Fisher and Nancy Frey’s Better Learning through Structured Teaching: A Framework for the Gradual Release of Responsibility (2021) offers a range of scaffolds to support learning across disciplines, with particular relevance to reading and writing.

Their model draws on several key theoretical foundations: Piaget’s (1954) work on cognitive structures, Vygotsky’s (1962, 1978) theory of the Zone of Proximal Development, Bandura’s (1965, 2006) research on attention, efficacy, retention, reproduction, and motivation, and Wood, Bruner, and Ross’s (1976) studies on scaffolded instruction.

From these foundations, Fisher and Frey propose an instructional model based on a “gradual release of responsibility” from teacher to learner, often summarised as “I do, we do, you do.” However, they emphasise that the process actually involves four distinct phases in the mainstream classroom:

I do it

We do it together

You do it together

You do it alone

In one-to-one contexts—such as parent-child learning or formal tutoring—the “you do it together” stage is obviously skipped, moving more quickly from joint modelling to independent practice.

Example: Teaching Persuasive TEEL Paragraphs

Phase 1 – I do it

Persuasive TEEL paragraphs aim to convince the reader of a certain point of view. Here’s a model topic sentence:

Dogs make great pets because they are loyal, friendly, and easy to train.

Phase 2 – We do it together

Now, let’s adapt the example. Imagine you want to convince someone that fish make great pets. Here’s your sentence starter:

Fish make great pets because…

Can you help me finish it?

Phase 3 – You do it alone (Using the Navigating Dysgraphia 5-Minute Sentence Timer)

Now, let’s try a new topic: art. I want you to convince me that paintings are amazing. Looking back at the dog and fish examples, write your own persuasive topic sentence.

This approach makes the learning process explicit and achievable, gradually building confidence and independence while modelling strong writing structures.

Adapting to the Student

The “gradual release” model is perfect for differentiated teaching of writing skills. Depending on the student and the goal, you can zoom in on sentence-level skills or progress quickly to full TEEL paragraphs.

My son, Ernest, for instance, moved quickly from single-sentence activities to writing full paragraphs using his TEEL checklist and timers, as the initial focus was on increasing the quantity of his writing before refining its quality. We’ve also recently added another self-regulating activity to the process—quality control through the “5-Minute Edit Checklist”. This helps him refine his work using a personalised set of mnemonic cues and metacognitive strategies.

As Fisher and Frey (2021) note, you don’t have to include a worked example for every session or every step in a single session. Once students have learned the skill, the aim is to transition them to independent capability. At home, I often set a simple topic — for example, a “Would you rather…” prompt—and Ernest uses his checklists and timer to self-regulate his writing.

Navigating Dysgraphia Program Summary here.

Ticking Minds: Sentence Level Scaffolds

Once students master the basics, instruction can shift to more complex writing skills—refining evidence, integrating analysis, and strengthening persuasive techniques.

Or, for creative writing, scaffolding might focus on vocabulary, such as adjectives, strong verbs, or adverbial starters. One of my favourite resources for this is The Student Guide to Writing Better Sentences by Ticking Mind (Pinnuck 2020).

I use this guide constantly—in my VCE English classrooms and at home with Ernest —because the scaffolds are just absolutely brilliant. Here’s an example from this book using pairs of adjectives strategy.

I’ve been using the 2nd Edition (Years 9–10), but I’ve recently discovered there’s also a Junior Edition for Years 7–8, which may offer better cross-application for upper primary activities. You can find more details and downloadable samples on their website here.

Navigating Dysgraphia Club Updates

This week, we welcome a new on-site member—a Grade 6 student—to the Mt Eliza Writing Studio Monday after-school writing club.

If you’d like to join us online, Navigating Dysgraphia Livestream Sessions begin Monday, 8 September:

4 PM AEST (Australia)

7 AM BST (United Kingdom)

Each group session runs for 50 minutes via Google Meet. The cost of the first three sessions is included in a basic paid membership. Founding Plan membership includes twelve one-to-one or group sessions. The program is designed for students in Years 3–6. If you’d like your child to attend, simply send me an email or message me via Substack. And if you’re in a different time zone but still keen to join, reach out—we’ll work something out.

Here to help,

Alexandra

English Teacher

Ph.D., MEd.

Subscribe for free to tag along as we explore, trial and test all things evidence-based (and occasionally quirky) to support kids with dysgraphia—one hopeful step (and story) at a time. Or go paid (for less than the price of a coffee per week) and access the Navigating Dysgraphia Club: a more personalised experience with bonus checklists, guidance, special events and a warm community cheering you on. All proceeds go directly toward supporting and sustaining the program.

References:

Bandura, A. (1965). Influence of models’ reinforcement contingencies on the acquisition of imitative responses. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. (6)1, 589–595. doi:org/10.1037/h0022070

Bandura, A. (2006). Toward a psychology of human agency. Perspectives on Psychological. Science. 1. 164–180.

Fisher, D., & Frey, N. (2021). Better learning through structured teaching: a framework for the gradual release of responsibility / Douglas Fisher and Nancy Frey. (Third edition.). ASCD.

Piaget, J. (1952). The origins of intelligence in children. New York: Norton.

Pinnuck, J. (2020). The Student Guide to Writing Better Sentences In the English Classroom. (Second Edition). Ticking Mind, Thornbury.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1962). Thought and language. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wood, D., Bruner, J. S., & Ross, G. (1976). The role of tutoring in problem solving. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 17(2), 89–100. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.1976.tb00381